The other night I did something I thought I never would.

I’d planned to visit a friend, a local kumu hula who’s in hospice care after braving many battles in a decade of war with breast cancer. But when I called the hospital, the nurse said she’d had many visitors already that day. She needed rest, so instead of going to the hospital I sat down at home in front of my laptop to spend the evening with what passes these days as sitting around the camp fire and talking story: Facebook.

Immediately, my eye was drawn to a post on a Hawaiian discussion group, a remarkable post that rekindled the internal debate that’s been burning in my naʻau (gut) for a couple of weeks now, ever since the big news came from the Office of Hawaiian Affairs.

Quite unexpectedly, OHA, whose trustees administer funds for the betterment of the Hawaiian people, the kanaka maoli, had announced a major change of course.

Rather than tacitly approving a nation-within-a-nation status for the Hawaiian people, a position inferred ever since the first introduction of the Akaka Bill in 2000, OHA said it will now commit to acting as a neutral party and facilitator of the nation-building process for creating what has been called the Native Hawaiian Governing Entity.

Up to now, the Native Hawaiian registry, called Kanaʻiolowalu, has been highly controversial in Hawaiʻi and especially so within the Hawaiian Sovereignty Movement.

As an advocate of the total independence of the Hawaiian Islands, I’d resisted the Native Hawaiian Roll Commission’s Kanaiʻolowalu registry for more than a year as OHA and the commission appeared headed toward a nation-in-a-nation, tribal status, for Hawaiians.

After all, it hasn’t exactly been a model of success for Native Americans, despite the fact that, since being “allowed” by the US to operate casinos in their so-called “sovereign” nations, some tribes are now faring very well economically. The big picture for Native Americans and their traditional cultures is bleak. The residual effects of their dealings with and treatment by the US government continues to extract staggering social tolls of unequaled poverty, widespread drug abuse and alcohol addiction, extinction of native language and arts and countless other diseases, physical and psychological, that come with colonization.

Should Native Hawaiians choose a tribal status, they can expect similar results.

Naturally, many in the Hawaiian Sovereignty/Independence Movement have opposed this path and resisted signing on to Kanaʻiolowalu.

But when OHA made its statement of neutrality and commitment to seeing the process through unbiased, I was among those who took this as a potentially good sign; especially when Bumpy Kanahele and Walter Ritte, revered leaders of the Hawaiian sovereignty movement, threw their support behind OHA’s effort. This was big. But for me, not big enough.

It was the post I saw on Facebook that night, with a link to the actual Kanaiʻolowalu Registry, that did it.

Seeing the names listed there, I couldn’t help but be in awe, despite the fact that the Kanaʻiolowalu signature campaign had been an unmitigated failure.

In a year, only about 20,000, out of about a half million Native Hawaiians living today, had signed.

Even after rolling over some 100,000 names from OHA’s earlier Hawaiian registries like Kau Inoa – whose rolls include countless Hawaiians now deceased – not even a quarter of the approximately half million living Hawaiians had enrolled.

Ostensibly, the roll was finally made public to allow Native Hawaiians the opportunity to confirm their signatures and those of their family members.

Still, the names drew me in. Maintaining my skepticism, I attributed my peeking at the traitorous palapala (paper) to the necessity of confirming that my own signature hadn’t somehow been added through these unsavory tactics. After perusing dozens of pages of “M” surnames, I was finally satisfied to see that “Milham” wasn’t there.

At this point curiosity took over. I scrolled through to “Mossman,” my mother’s maiden name, and came up with nearly two entire pages of names- almost all, surprisingly, were ʻohana I’ve never even met. Their residences were all over the place. Imagining the future family reunions, I quickly copied the link to the page and pasted it in our Mossman ʻOhana Facebook page.

The one name I didn’t see, the name I was looking for, was my mother’s: Dallas Kealliihooneaina Mossman.

Although she passed in 1996, and I was pretty sure she would not have signed Kau Inoa, I recalled her having urged me to sign an earlier registry back in the 80s. So I searched again, this time, under her married name, “Dallas Kealiihooneaina Mossman Vogeler.”

There it was.

Seeing my mother’s name, struck me as deeply as when I found my great grandmother’s name, Rebecca Mellish Mossman, on the Kuʻe Petitions of the Hui Aloha ʻAina o Nawahine.

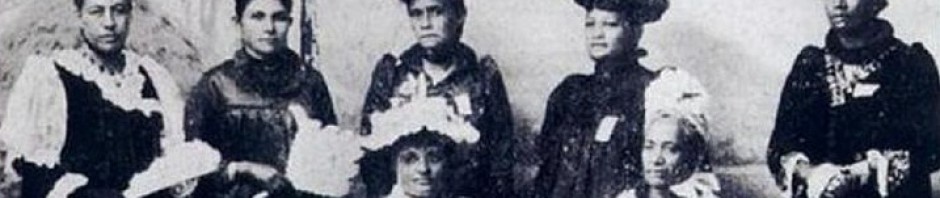

Like my mother, these women – Emma ʻAima Nawahi, Abigail Kuaihelani Campbell and the others you see above you on this blog whose brave leadership stopped the treaty of annexation of Hawaiʻi to the U.S. with their 1897 petition – have been a guiding light, inspiring me since 2010 to share their story, with the historic re-enactment “Ka Lei Maile Aliʻi: The Queen’s Women,” with audiences throughout the Pacific Northwest.

Scrolling further through the Ms, I found the name of my friend in the hospital, Gina Kaleialoha Mahiai. I thought of how she stood on stage beside me in 2011 during a performance of “Ka Lei Maile Ali’i” at the 3 Days of Aloha Festival at Esther Short Park in Vancouver, Washington.

I remembered how she shined, playing the part of Kuʻaihelani Campbell, delivering her lines in ʻōlelo Hawaiʻi with passion, going into the audience to hand out her pretend petitions. How she called out to them, ” E hele mai!,” to join us on stage to sing “Hawai’i Ponoʻi.” And I pictured again in my mind how the people came and we all held hands in unity of spirit because of her singular gesture of pure aloha for the Hawaiian people.

The Women of Hui Aloha ʻAina, like my mother and Kaliealoha Mahiai, were not apathetic. They not only stepped up to be counted, they led their people.

Even knowing my mom’s signature was given on an earlier roll, and not Kanaiʻolowalu, seeing her name was the catalyst I needed at the exact moment I needed it. It was her determination to be counted among her people, that I couldn’t deny.

And so after years of marginalized existence as one of the quarter million Native Hawaiians on the “mainland,” historically denied our birthright as “beneficiaries” of OHA, I had an epiphany. It was up to me to decide whether or not to be heard. If I do not grab hold of this opportunity to speak, to express my opposition to tribal, nation-in-a-nation status for Hawaiians, who will?

If I don’t do all I can, to share my manaʻo – that total independence is the only viable option for the future our ʻaina (land) – then I will have abdicated my kuleana, my responsibility. I will have failed, not only my mother and the women of Hui Aloha ʻAina o Nawahine, but my own future grandchildren and all future generations of kanaka maoli for whom this ʻaina is their birthright.

With these thoughts suddenly clarified, I found myself digging through my files for birth certificates documenting my ancestry. And then, with a click of a button, I signed the Kanaʻiolowalu registry.

I signed. And when I woke up the next morning, I had no regrets. Rather, I was inspired again – by women like Kaleialoha and my mom who refused to be silent or stand aloof from our process of nation building – and hopeful at the prospect of carrying on their determination of claiming a voice in the future of the Hawaiian Nation.